Product taxonomies are critical to the customer experience on ecommerce platforms, marketplaces and websites. In order for customers to find the right product, they need to intuitively navigate the product hierarchy, browse through product categories, locate the product type they are interested in, use product attributes to narrow their selections and locate the precise product content that will help them decide what to ultimately purchase. Product taxonomies therefore must be carefully planned, through a structured taxonomy development process using product taxonomy best practices. Proper taxonomy development ensures that customers can locate a specific category of product more quickly and easily.

The taxonomy structure enables product discovery and informs the organizing approaches behind product categories. It is foundational to attribute design, and informs product classification using metadata models (also referred to as product data models) and tagging of product content. The correct categorization enables the on-site search engine to retrieve appropriate results from the product catalog.

Product content consists of the assets that help customers make purchase decisions. This supporting content might include an installation or troubleshooting guide, a product description more detailed than the one on the landing page, and images, brochures, or other information that is not a direct description of the product itself. Frequently these digital assets are created by product management teams who understand the needs and buying habits of the customer, and know how to integrate this information seamlessly into the customer experience – frequently using artificial intelligence for personalization. Related content might include a similar product, related product groups, or complementary products from relevant categories or an entirely different category. Content tagged with a product category can support multiple products in that category, which results in efficient use of content. The categorization process is at the core of the customer experience and allows customers to discover information to support their purchase decision.

If you Google “taxonomy” the first definition is “the branch of science concerned with classification, especially of organisms.” However, taxonomy also plays a crucial role in the context of business as a system of hierarchical classification.

Taxonomy has many uses in business. It is used in terms libraries for search engines, information architecture behind AI applications such as chatbots, or to index knowledge such as company documents. Customer taxonomies assist in understanding behaviors for engagement.

Some companies attempt to use one taxonomy for multiple purposes, but this is a mistake that is fraught with inefficiencies and problems. It is much better to develop multiple taxonomies, with each specialized to a purpose or dimension based on a domain model. (Relationships among them can be established later to create an enterprise ontology.) While one broad purpose is organizing product data for commerce applications, specific types of product taxonomies are used to support different use cases from financial management to product attribute design and product classification, navigation structures, distribution through partners and publishing processes. Each scenario has different purposes, requiring a more nuanced approach to the product taxonomy development process.

In this article, we’ll focus on 5 taxonomies related to the product data in your ecommerce processes, their purpose and key best practices for maintaining them:

- Reporting

- Attribution

- Navigation

- Syndication

- Publishing

Reporting Taxonomy

This taxonomy is commonly used in Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems. Its main purpose is to help streamline operational, supply chain, and fiscal reporting data. This type of taxonomy is usually organized by an internal company structure that aligns with operation or sales reporting. ERPs often have a fixed hierarchal depth, so each level has an overarching level assignment such as Company - Division – Family – Product – SKU. This structure allows for ease of reporting and clear instruction to governance but can get messy because some levels may not have a clear value, resulting in duplication of values. The hierarchy must be designed correctly and evaluated for the necessary depth. Some companies may need only a three-tier hierarchy, while others may need a six-tier hierarchy, depending on the complexity of the company and its products.

Attribute Taxonomy

This taxonomy is often the backbone taxonomy in a Product Information Management (PIM) system (PIM) or Master Data Management (MDM) system, and is used to organize category-specific attributes. It is organized by “is-ness,” which is how we refer to organizing by what a category factually represents, not what it does or how it is used. An example of this can be illustrated with hinges.

If hinges are organized by is-ness, then we may see the following path “Hardware > Hinges” but if we allow a particular use to come into play, the category may split between “Door Hardware > Hinges” and “Cabinet Hardware > Hinges.” We now have hinges in two locations because the taxonomy wasn’t focused on a primary organizing principle of is-ness. A better way is to organize hinges with an attribute of “hinge type” for example. This is the “about-ness” – a characteristic of the item to differentiate from another.

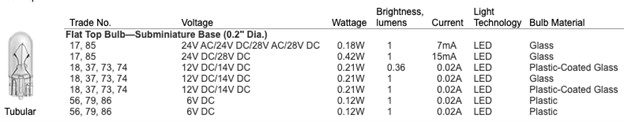

Is-ness allows for a clean and consistent structure that allows for attributes to be managed from the global to terminal level. On the global level you may see attributes such as “Brand” and “Price.” These are other examples of “about-ness” attributes. If we have one hundred products that are the same type of thing we can differentiate them by type, by brand, price and other descriptors. These descriptors allow for filtering and refinement of choices. As you go down the structure the attributes get more specific. A lightbulb may have other about-ness attributes assigned at the terminal category level such as “Voltage” and “Light Technology,” as shown below, whereas a sawblade would have attributes such as “Number of Teeth” and “Hook Angle.”

Some key best practices when managing an attribute taxonomy include mutual exclusivity, which refers to having one product in one place. An item or SKU can only be classified into one category. Conversely, this taxonomy also must be exhaustive, providing a category that provides attribution for all items. Labels should be clear and concise without attributes or company jargon such as brand or family name stuffed into the labels.

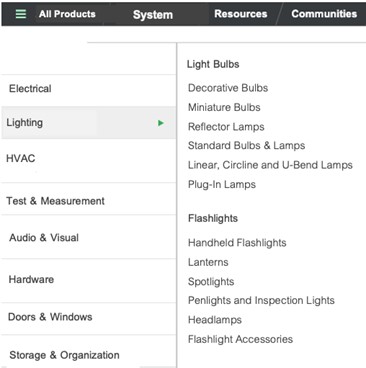

Navigation Taxonomy

A navigation taxonomy is used on an ecommerce site and is primarily focused on findability. The primary product taxonomy is usually organized by is-ness, but there are possibilities of secondary taxonomies, allowing for additional organizing principles such as application, industry, or persona-based taxonomies.

This enhancement allows the ecommerce site to provide multiple ways the customer can shop for products. The primary is-ness structure can start with the same taxonomy used in attribution, but then it needs to be adjusted for findability. Categories of higher priority should be raised to the higher levels of the taxonomy, while lower priority categories can be deeper in the hierarchy.

Poly-hierarchy that allow for categories to be in multiple locations and junk drawer categories like “Other” should be avoided. The taxonomy should be tested to find weaknesses in the structure; that can point to areas where the taxonomy can be optimized.

Syndication Taxonomy

Syndication Taxonomy

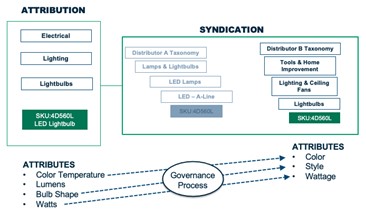

This taxonomy is used for managing incoming and/or outgoing product information. If product data is being sent to a distributor such as Amazon or Grainger, this structure allows mapping from your attribution taxonomy to a mirror of the distributor’s taxonomy and allows mapping of the attributes in that taxonomy.

The attributes may not be a simple one-to-one map, so some rules may be needed to flag situations in which a format differs from the distributor’s to allow for adjustments. Your attributes may have a temperature range, while the distributor separates this “Temperature Range” out into two attributes for “Minimum Temperature” and “Maximum Temperature,” for example. This adjustment works similarly for incoming data. If you have suppliers providing data, a syndication taxonomy can be used in a supplier portal to allow for the data to be mapped into your attribution taxonomy.

Publishing Taxonomy

This taxonomy organizes the categories and items inform different publications such as catalogs, flyers, or customer-specific product offerings. It can be managed in a PIM, MDM, Publishing system or even a customer relationship management (CRM) system. This approach allows the use of templates to lay out a print page and users to drag and drop products or categories into that template as needed. The data is mapped from the attribute taxonomy without modifying that taxonomy.

Each of these taxonomies has a clear purpose and organizing methodology. They each support the business in different ways and have their own importance. The design, development, and application of these business-critical taxonomies requires unique approaches to ensure that taxonomies are correctly optimized.

Is it Better to Buy or Build Your Taxonomy?

Some believe that the best approach is to use a standard taxonomy or modify an existing taxonomy from a public source. The challenge with using someone else’s taxonomy is that product navigation, product attribute design, and product categorization should be based on what is important to your customers and aligned with their “mental model” – how they think about solving their problem and how they think about your products and services.

Using a Google product category structure might meet the needs of a general audience but not necessarily your particular audience – your customer. Standards can support Google shopping applications and provide efficiencies, making it easier to list products for Google shopping, but using a standard classification and navigation scheme does not differentiate the customer experience. Standardization is for efficiency; differentiation provides competitive advantage.

It is best to build an original taxonomy in order to own and optimize the customer experience for your product catalog. Product data management is at the core of a differentiated customer experience. Product teams and merchandizers need to understand these core principles to ensure that metadata tags are correct given a product type, that the subcategory structure makes sense relative to a given top level category, and that categorization of related content is aligned with the overall product taxonomy structure.

Ready to get started? Contact us to learn how we can help.